Bill Sayle was a professor at Georgia Tech. He passed away earlier this year; I found out via a mention in the national IEEE newsletter (page 17 of this PDF), and then earlier this summer the GT ECE newsletter featured an article about him (page 3 of this PDF).

I have to admit that I did not know him that well, but 15 years ago he had an impact on the direction of my career.

From 1985 to 1990 I attended Georgia Tech in pursuit of a degree in Aerospace Engineering (AE). I exhibited rather lackluster performance in acquiring my degree, basically slouching my way through 5.5 years of studies. The truth is, I found many other things much more interesting, and just didn’t really care that much about AE. It didn’t help that the aerospace industry had tanked in the late 80’s as the end of Cold War paid a peace dividend and the defense industry shriveled. But I can’t just blame the industry for my inability to find AE work; my GPA was definitely crap, mostly weighed down by 3 or so years of serious slacking off. It was only in the last 2 years or so of getting the AE degree that I really started trying, but at that point I had so much weight on my transcript that I could only pull my GPA up to a 2.4 . Georgia Tech is a hard place, and AE one of the hardest degrees, but that’s still rotten.

So I graduated (in Dec 1990) and started working full time. As a temp slave. Seriously, I had an AE degree from Georgia Tech — one of the most difficult degrees from one of the most difficult schools in the country — and I was working as a filing clerk at a government office downtown via a temp agency. I discovered that year how little I needed to survive, because I made $11,000 that year, and that paid for everything, including rent and car insurance. I made the best of the job (eventually developing some procedures and computer tools for them) but kept on looking for “real” work. This went on for a whole year.

Finally in early 1992 I got a job as a field engineer with a company in the Atlanta suburbs that did contract work in the nuclear power industry. They simply accepted anyone with a GT degree and then trained them to do the field work. And off I went to nuclear plants around the country. Some other time I’ll write about my experience working in nuclear power.

In 1994, I had been out of college and in the workforce for 4 years. Knowing that Georgia allowed you to claim in-state status (and the ridiculously cheap tuition rate) after 3 years of non-student residency, I had my eye on returning to Georgia Tech to get another degree. At one point in my life I had fantasized about doing this endlessly, working and going to college and just accumulating degrees, but these days I’ve happily put my academic life behind me. So anyway, at the time I was thinking about going back to Tech. I quit the nuclear job in Dec 1993 and took a month or so off to relax, do all those things I would do “if I just had the time” and think about what I would do next. ( I learned something about myself in those 1-2 months: left without constraints or demands, I don’t get much done.)

I decided to indeed go back to Tech fulltime and get an Electrical Engineering degree, but a Bachelor EE degree, not a Masters EE. I had become interested in EE as a utilitarian degree, one that I could apply at home and in the community, certainly moreso than one can apply an AE degree. So I really wanted to learn the basics of EE, not study some EE niche as a master’s student.

Getting a second bachelor’s degree brings up a bit of institutional bureacracy. Georgia Tech allows you to apply credits earned at any time over the past 10 years to any degree, so I could use all those basic course credits (Calc, Physics, English, etc.) accrued during my AE studies in the 80’s and apply them to an EE degree. I just had to take all the EE courses, about 80 credit hours worth, which it turned out would take about 18 months of fulltime study. I had started at Georgia Tech (and received my first course credit) in 1985. If I was starting this work on the second degree in 1994, and it was going to take me 18 months, and I needed to take a quarter off in the middle somewhere to make some money, I was going to be in a bind. By 1996, the 10-year sliding window was going to start killing my first credits from 1985 and 1986 — basic courses that I certainly did not want to have to take again. I needed an 11-year window.

And so that’s where I was in February 1994. I wanted to A) get accepted back into Georgia Tech to get a second degree, and B) I needed a waiver from them for the 10-year window, just a slight extension. And remember that my first tenure with Georgia Tech was rather unimpressive — I barely got out of there with my AE degree, with a truly awful GPA.

So with all that in mind, I wrote a letter to Bill Sayle, laying out this situation and requesting admission and the waiver. To my delight, I guess he saw my potential and said that A) they’d admit me and B) he’d endorse my waiver request. To be fair, I realize now that older students are safe bets, because they’ve crossed that maturation threshold that is hit-or-miss with regular college-aged students.

I made some contacts in the nuke industry and started coordinating some nuclear contract work (1-2 months at a time) to fit into the school schedule. Over the next two years just two of these contract jobs paid for the study months (rent, food, tuition, etc.) They were very hard work, with 72-hours weeks (the regulated maximum allowed) but with very good pay, enough to pay for my expenses for the rest of the year.

Exactly 2 years later, in March 1996, I finished my EE degree and started working at Scientific Atlanta as an electrical engineer. Unlike my first time through Tech, this time I’d done fantastically well, landing on the Dean’s List every quarter. Considering my poor performance the first time, I’m pretty proud of that. So I like to say that I’ve been on both sides of the academic fence — the smartass slacker in the back of the room who barely survives to get the degree, and the smartass brown-noser in the front of the room who takes furious notes, engages the professor a lot, ruins the curve and gets the honors.

Bill Sayle was a small but critical part of that transformation, and I thank him for it. RIP.

He took her to the airport, where they watched the planes coming in to land. They flew right over their heads! It was very loud, and Flat Bridget wanted to cover her ears.

He took her to the airport, where they watched the planes coming in to land. They flew right over their heads! It was very loud, and Flat Bridget wanted to cover her ears. Flat Bridget went with Uncle Chris and Aunt Sharon

Flat Bridget went with Uncle Chris and Aunt Sharon  to visit some friends who had two new kittens. The kittens liked Flat Bridget so much they stood right on top of her! Then Flat Bridget got to meet

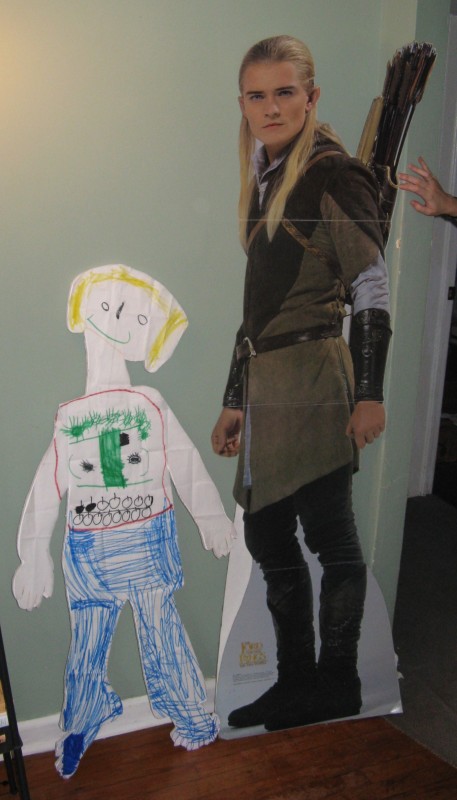

to visit some friends who had two new kittens. The kittens liked Flat Bridget so much they stood right on top of her! Then Flat Bridget got to meet  Flat Legolas from a famous movie about hobbits. She even had a chance to play the drums!

Flat Legolas from a famous movie about hobbits. She even had a chance to play the drums! but there was nobody there. They did get to look through the fence at the giant baseball. Play ball!

but there was nobody there. They did get to look through the fence at the giant baseball. Play ball! Flat Bridget then went to visit Eyedrum, which is a place that Uncle Chris likes to go to.

Flat Bridget then went to visit Eyedrum, which is a place that Uncle Chris likes to go to.  When Uncle Chris wasn’t looking, she climbed up on the silo out front — Flat Bridget, get down from there!

When Uncle Chris wasn’t looking, she climbed up on the silo out front — Flat Bridget, get down from there!  Then they went inside, where Flat Bridget looked at strange art and then

Then they went inside, where Flat Bridget looked at strange art and then  got up onto the stage and spoke her mind!

got up onto the stage and spoke her mind! downtown to work with Uncle Chris. She played on the big CNN sign with another little girl who was also visiting, and then

downtown to work with Uncle Chris. She played on the big CNN sign with another little girl who was also visiting, and then  she watched some people announcing the news like they were on TV.

she watched some people announcing the news like they were on TV. She wanted to run into the fountains with the other children but Uncle Chris said “Flat Bridget, you are made of paper!” and would not let her go in. Look at the tall skyscrapers! See how some of the windows look different? A very strong storm called a tornado came through downtown Atlanta and broke many windows in the skyscrapers. But nobody was hurt and they are now fixing all of the windows.

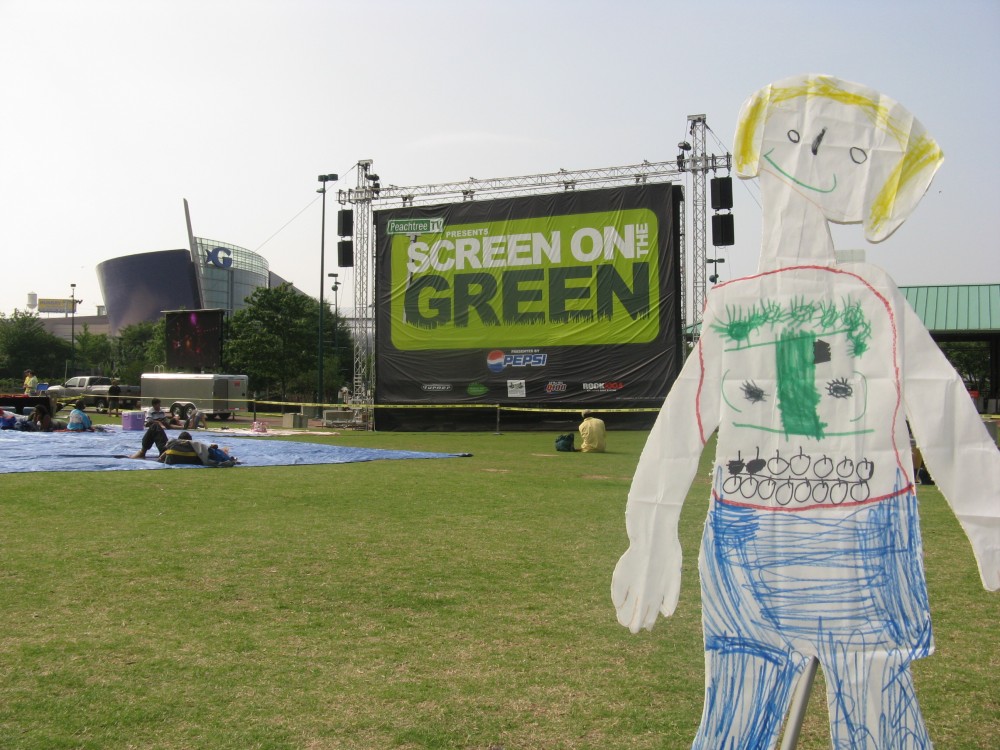

She wanted to run into the fountains with the other children but Uncle Chris said “Flat Bridget, you are made of paper!” and would not let her go in. Look at the tall skyscrapers! See how some of the windows look different? A very strong storm called a tornado came through downtown Atlanta and broke many windows in the skyscrapers. But nobody was hurt and they are now fixing all of the windows. Later that night there was going to be a movie in the park, but it was going to be a famous movie about a big shark. Shark movies can be scary so Flat Bridget didn’t want to see it. But in the distance, can you see the building with the “G” on it? That is the Georgia Aquarium, and Uncle Chris is going to take Real Bridget there when she comes to visit Atlanta. Lots of fish and sharks and whales and dolphins and all kinds of water creatures!

Later that night there was going to be a movie in the park, but it was going to be a famous movie about a big shark. Shark movies can be scary so Flat Bridget didn’t want to see it. But in the distance, can you see the building with the “G” on it? That is the Georgia Aquarium, and Uncle Chris is going to take Real Bridget there when she comes to visit Atlanta. Lots of fish and sharks and whales and dolphins and all kinds of water creatures! Next Uncle Chris took Flat Bridget to another place that he works. It’s a place called a teleport, where they have many big satellite antennas that are pointed at the sky. The antennas are talking quietly to the satellites very high in the sky, much higher even than airplanes.

Next Uncle Chris took Flat Bridget to another place that he works. It’s a place called a teleport, where they have many big satellite antennas that are pointed at the sky. The antennas are talking quietly to the satellites very high in the sky, much higher even than airplanes. Flat Bridget came back home with Uncle Chris and Aunt Sharon, where their cats Maggie and Penny were very curious about the new stranger in the house and spent a lot of time sniffing and exploring.

Flat Bridget came back home with Uncle Chris and Aunt Sharon, where their cats Maggie and Penny were very curious about the new stranger in the house and spent a lot of time sniffing and exploring.  After a while we could see that Maggie liked Flat Bridget very much!

After a while we could see that Maggie liked Flat Bridget very much!

Which basically consisted of taking a ferry from downtown Auckland to the island of Rangitoto in the bay. Rangitoto formed out of thin air (well, sea water) as a new undersea volcano erupted about 600 years ago and thrust this new island up out of the water. It’s a couple miles around and has the familiar cone at the center, albeit a small one.

Which basically consisted of taking a ferry from downtown Auckland to the island of Rangitoto in the bay. Rangitoto formed out of thin air (well, sea water) as a new undersea volcano erupted about 600 years ago and thrust this new island up out of the water. It’s a couple miles around and has the familiar cone at the center, albeit a small one.  What’s really amazing about this island is that the lava hasn’t broken down into soil yet, so most of the island is covered in this surreal deep-black fluffy-looking stuff that is actually volcanic rock. In some places a couple inches of soil has formed (starting with lichen on the rocks) and so you do have some plant life. But mostly it’s either bare black fluffy rock moonscape (despite 600 years of weathering) or overgrown with low plants that can eke out a life on the meager soil so far.

What’s really amazing about this island is that the lava hasn’t broken down into soil yet, so most of the island is covered in this surreal deep-black fluffy-looking stuff that is actually volcanic rock. In some places a couple inches of soil has formed (starting with lichen on the rocks) and so you do have some plant life. But mostly it’s either bare black fluffy rock moonscape (despite 600 years of weathering) or overgrown with low plants that can eke out a life on the meager soil so far.  So in contrast to our self-guided travels for this entire trip, today we paid for the ferry ride out and went on a guided tour of the island. We piled into this tractor-trailer rig (with mostly retirees and toddlers) and went on a slow and impossibly bumpy ride around the island, with commentary by the tractor driver up front.

So in contrast to our self-guided travels for this entire trip, today we paid for the ferry ride out and went on a guided tour of the island. We piled into this tractor-trailer rig (with mostly retirees and toddlers) and went on a slow and impossibly bumpy ride around the island, with commentary by the tractor driver up front.

Today was the big drive back east across the island to Christchurch to return the campervan and fly to Auckland. The drive was uneventful, except for when we had to drive through a treacherous gorge that was part of the pass (“Arthur’s Pass”) through the mountains. There had been signs for an hour discouraging people from towing a trailer through the pass. On our way into the mountains we were passed by ambulances and fire engines with sirens blaring. AN HOUR LATER we reached the gorge, where a sedan towing a trailer had hit the guardrail and nearly plunged to their deaths. It was an extremely remote place, just about the worst part of the entire pass, certainly with no cell phone coverage, and we wonder how long the accident wreckage was in place until word reached the emergency services to fire up their engines. As we passed them, finally, we all glowered at the college-aged morons who had created their own misery … The picture above was taken right after we reached the top of the pass, only a minute after getting past the accident site. That’s a permanent snowcap at the top of the mountain.

Today was the big drive back east across the island to Christchurch to return the campervan and fly to Auckland. The drive was uneventful, except for when we had to drive through a treacherous gorge that was part of the pass (“Arthur’s Pass”) through the mountains. There had been signs for an hour discouraging people from towing a trailer through the pass. On our way into the mountains we were passed by ambulances and fire engines with sirens blaring. AN HOUR LATER we reached the gorge, where a sedan towing a trailer had hit the guardrail and nearly plunged to their deaths. It was an extremely remote place, just about the worst part of the entire pass, certainly with no cell phone coverage, and we wonder how long the accident wreckage was in place until word reached the emergency services to fire up their engines. As we passed them, finally, we all glowered at the college-aged morons who had created their own misery … The picture above was taken right after we reached the top of the pass, only a minute after getting past the accident site. That’s a permanent snowcap at the top of the mountain.  Then we passed through the very arid region east of the mountain peaks, which provide more starkly beautiful views, including this one of a small lake with whitecapped waves on it because the wind was so strong! Below is a 360-degree panorama, which Chris likes doing if only to watch Sharon roll her eyes. Obviously you can’t make out much in this web version, even if you click below to get the enlarged version … At full resolution they are stunning … we’ll have to get these printed as blowups.

Then we passed through the very arid region east of the mountain peaks, which provide more starkly beautiful views, including this one of a small lake with whitecapped waves on it because the wind was so strong! Below is a 360-degree panorama, which Chris likes doing if only to watch Sharon roll her eyes. Obviously you can’t make out much in this web version, even if you click below to get the enlarged version … At full resolution they are stunning … we’ll have to get these printed as blowups.